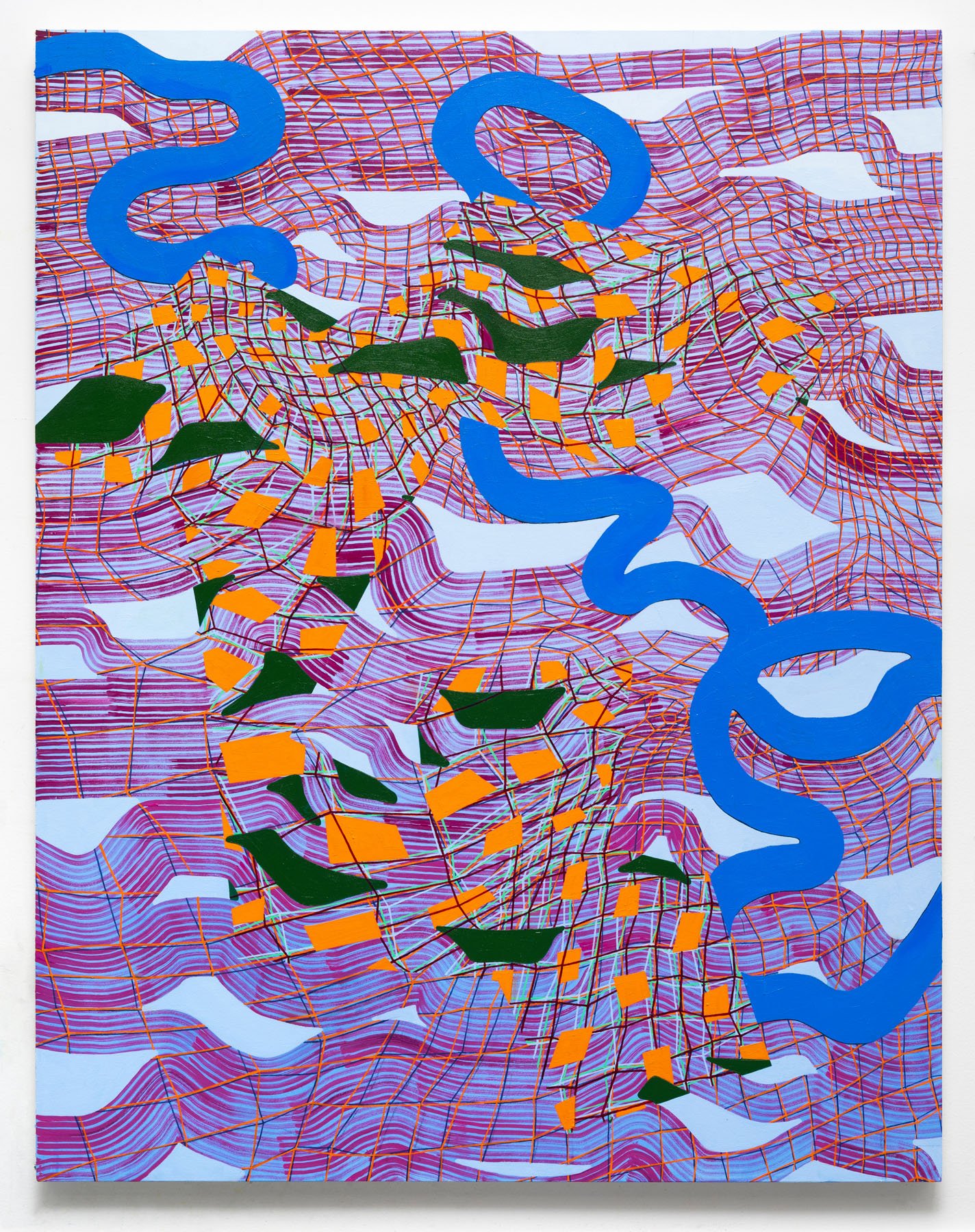

Lisa Corinne Davis, Registered Impersonation, 2020, acrylic and oil on paper, 14 x 12 inches

Contributed by Sangram Majumdar / Lisa Corinne Davis, whose solo is on view at Pamela Salisbury through November 2, is an abstract painter who is known for her engaging explorations of map imagery, codes, and drawing systems. Recently she has been thinking about the destablization resulting from Covid, politics, and the current cultural focus on race and identity. “The paintings are really an abstract manifestation of the psychological places I’ve existed in,” she told me, “not a politicized statement of what you may not see or may not know about me….All of a sudden, for the first time in my life, I’m a ‘black woman,’ writ large – because of current culture.”

Sangram Majumdar: Let’s start with the title of your exhibition “All Shook Up” currently up at Pamela Salisbury Gallery in Hudson, NY. Why Elvis?

Lisa Corinne Davis: So the title “All Shook Up” is twofold. On one hand it’s talking about the cultural time we’re in, that we’re all kind of shaken up by COVID, politics, racial unrest, et cetera, but also refers to the deep destabilizing force in my work. There is no terra firma. In general, I’m trying to shake up systems, like the system of decoding race. This always comes from a personal place for me. Throughout my life and no matter how long people have known me or talked with me, at some point they say, “well, what are you?”

I’m thinking “I’m the person you’ve been having a relationship with and so forth for God knows how long!” There’s a series of codes that they’re trying to apply to me, like blackness, whiteness, mixed, urban, provincial. People do it all the time in order to have a quick, firm footing into accessing a person.

I want to destabilize this, in a kind of abstract sense, so that all orientations of perception, whether it’s aerial or micro or macro or a facade is mixed. You can never quite stay put.

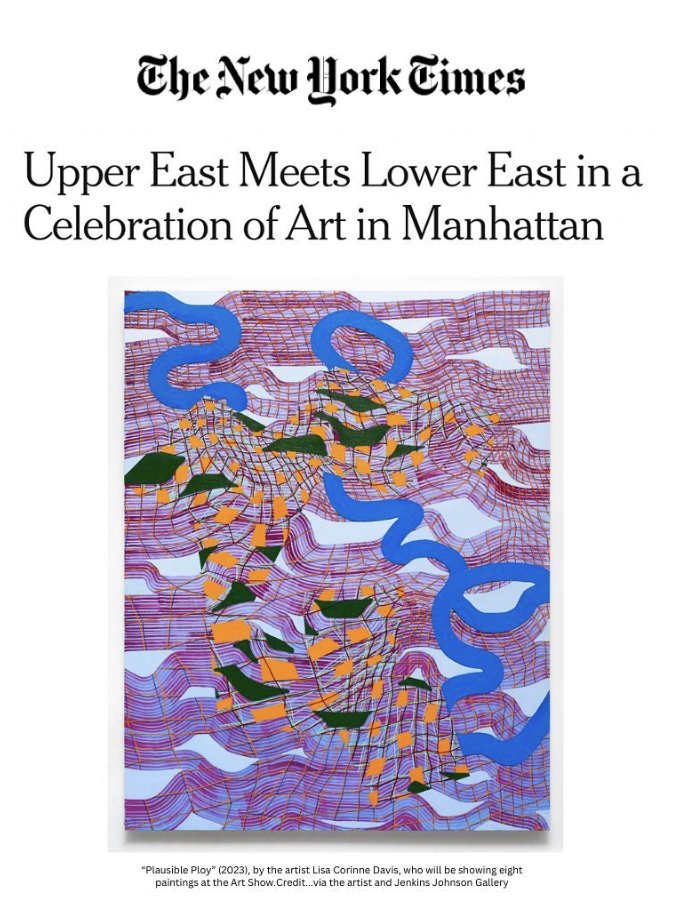

Lisa Corinne Davis, Miraculous Measure, 2020, oil on panel, 40 x 35 inches

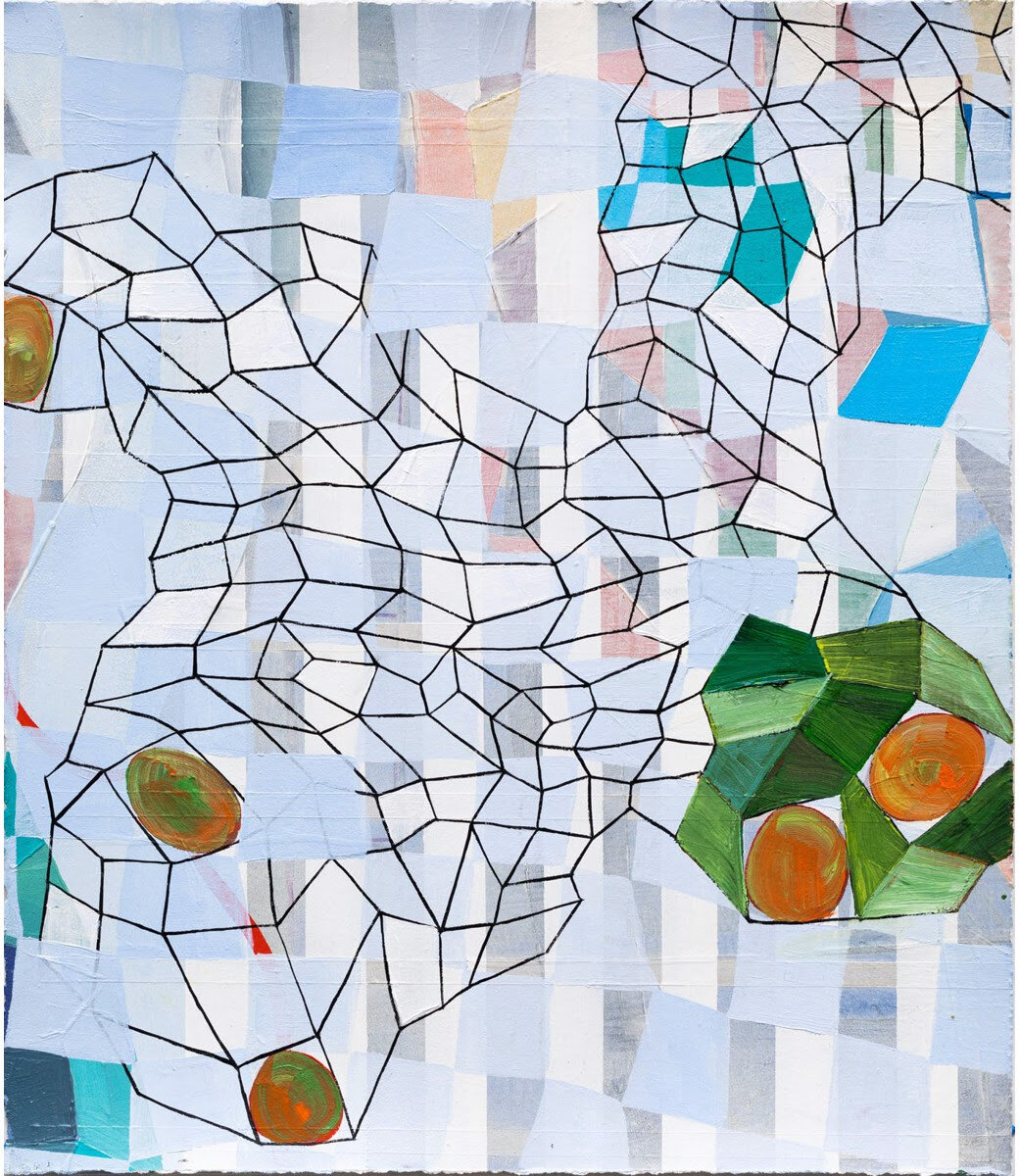

SM: I completely see what you mean in terms of destabilization. In Miraculous Measure, 2020, the floating rectangles hint seem to suggest that they are pieces from a large shape, one that’s being subdivided or expanding beyond the frame. And the spiraling structure in Spineless Scheme II, 2020 is destabilizing in a different way. It made me think of what it would feel like to experience loss of gravity, as if suspended in air or water. It’s a very disorienting space that you create, but there’s a precision and clarity to the structures.

LCD: I lean on structure because the structure is the boundary. Like in culture too. And if a grid is supposed to behave a certain way in a painting, like as a democratic surface, oriented, a measured zone, how can I make it not quite do that? I don’t completely tear it apart, but also I’m just not going to quite play by the rules that are given here.

Everything I start with in the painting I try to make it misbehave as it travels, disobeying the codes that the painting is supposed to adhere to. So, again, with linear perspective, things seem to be going back towards a point on the horizon, well, that’s the rules of the game. But I’m going to say, well, what happens if you just kind of step slightly aside from that?

Lisa Corinne Davis, installation view at Pamela Salisbury

Lisa Corinne Davis, Spineless Scheme II, oil on panel, 27 x 20 inches

SM: Your paintings seem to be calling attention to how things actually are, how a system is altered in real time, in real space, as opposed to its planned ideal.

LCD: Right, exactly. And again, back to the parallel to the personal. So this black girl, you know, ended up at the Quaker private school and living in the Orthodox Jewish neighborhood.

SM: So how do you construct these paintings? How does the subjective and objective aspects of your thinking and making come together?

LCD: Lately, I’ve been starting with a field of color, pretty warm, hot color, because I’ve been interested in losing that back plane of the canvas as much as I can to light. So I tend to start with a color and then I just start weaving. Let’s say I’ll start with something more geometric and then I will have a conversation with the organic and try to disrupt what I started.

SM: This idea of a ‘conversation’ also seems to play out metaphorically between the word pairs in your painting titles.

LCD: I have these running lists of words. Some of them I think of as objective words, like rules or graphs or measures. And I have this other list of what I think of as subjective words, words which are more psychological. I put them one next to the other, so one is disrupting the other in the title.

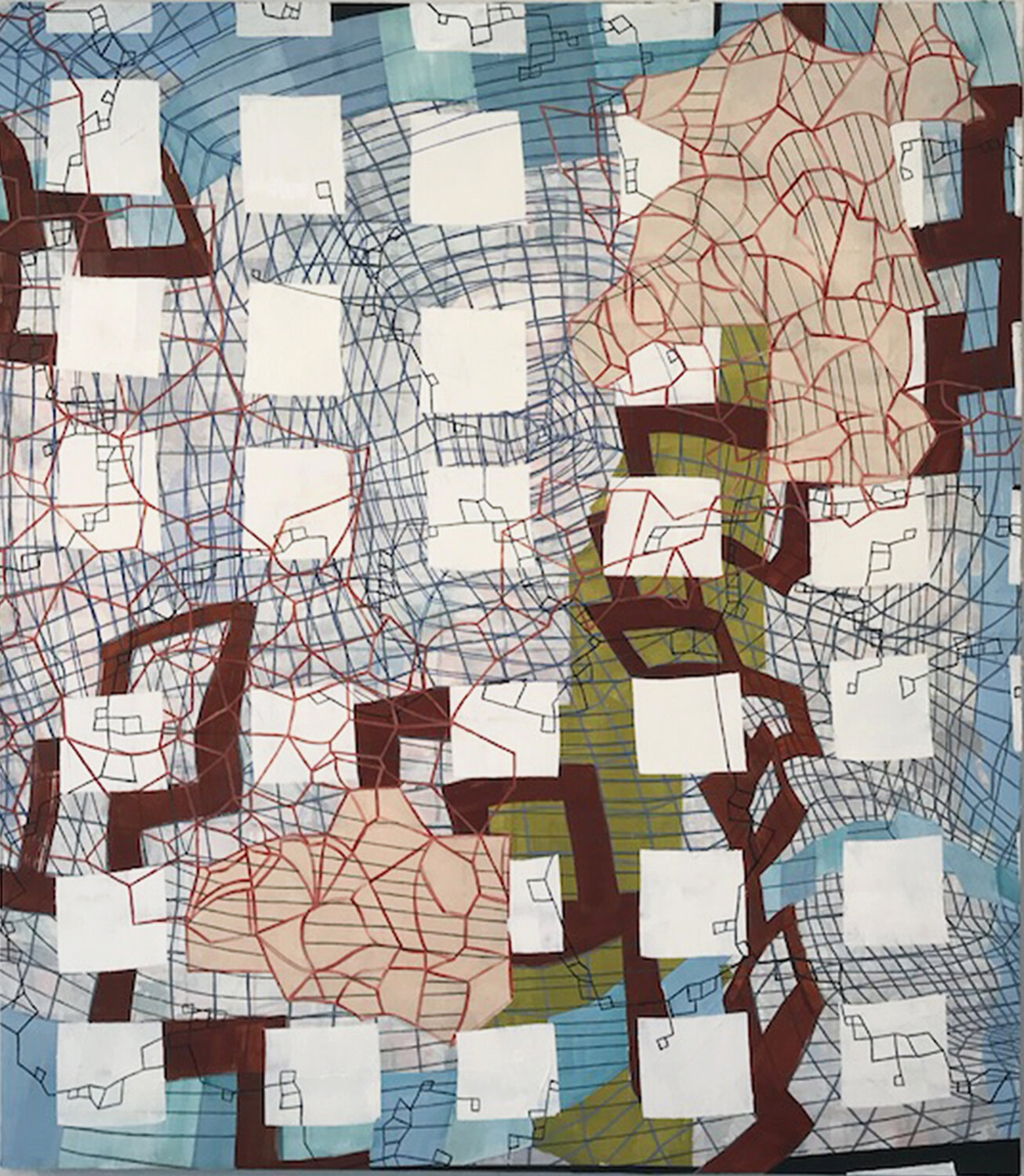

Lisa Corinne Davis, Phantasmal Placement, 2018, oil on panel, 48 x 36 inches

SM: In a lot of the recent paintings, there’s a blue-green-gray that I associate with the map reference. But it also brings up ideas about atmosphere. And then these bursts of color, like words, like confetti come to my mind. In Phantasmal Placement, 2018 I think of kites in the sky. There’s an incredible amount of space between the multi-color form on the top to the one in the middle. The space feels vast.

LCD: The colors also refer to suggestions of lived locations and also mapped locations. When we think of map colors, it’s primarily yellow, blue, red. They’re kind of, you know, these kind of soulless colors. And then we have colors that are truly visceral suggesting toxicity or luminosity or spectacle. I try to use both in a painting and again, sometimes I use it in an alignment with those subjective or objective spaces or places or suggestions, and sometimes I just use it as a disruption, a disruptive component.

Years ago, I got very interested in Aboriginal painting, and how they are constantly working around the canvas, working around the surface. So I keep going until there’s enough spatial reads, orientations and that there’s some shift from a macro to a micro view of something. Sometimes they go too far and they get sanded down. And then I use that as the clue to starting the conversation again.

SM: That idea of working from a residue seems particularly visible in paintings like Spineless Scheme II, 2020. Are there ever associations that you start seeing in the paintings, either metaphorically or visually, that you don’t want in your work?

LCD: No, I actually don’t ever go there. I know things that people have said, biological organs and, you know, certainly references to landscape elements and or street elements or – but I’ve never consciously thought of that. Social, racial, gender issues are all going to mix with what you come away with. I can’t and don’t want to take that from you and I didn’t want people to take it from me. I sometimes wonder if references should be more evident in the paintings, but I think for now I’ve decided it becomes too political. The paintings are really an abstract manifestation of the psychological places I’ve existed in, you know, not a politicized statement of what you may not see or may not know about me.

SM: You are talking about time and memory and the past. How did this body of work begin?

LCD: When my children were born I began making ink self-portraits and I would cover them with graphite. So when you looked at them, you could only see a kind of glimmer of a person below a semi reflective surface. Simultaneously, I also started to think about the appearance that I’ve dealt with my whole life. I was thinking about the appearance of what my first child would be with a white Canadian husband. What is this kid going to look like? Me? And then I thought, well, what will be the difference if he looks like X or Y or Z? What will that mean for his life? So that got me interested in people’s ideas around visual cues and determinations of behavior around culture and race. These ideas could not be expressed literally in a painting. There was no other language than abstraction that seemed to make sense.

SM: So it’s almost like what’s behind that graphite drawing has become the subject matter and you’ve jettisoned the representational signifiers whose primary function was to call attention to the image, like a “come here” sign or something.

LCD: Yeah, exactly. You couldn’t have said it better.

SM: The titles of your paintings also seem to be a “calling out” of sorts. Through titles like Schematic Sham, Bogus Basis, Registered Impersonation, (all 2020) we get a sense of what’s happening in the world or maybe how you feel about it.

LCD: Some people never really registered the titles and some people like you see it immediately as part of the plan here. But yeah, I work with fixed identity on many levels.

I think that’s a thing that happens when you don’t grow up with a clear, firm cultural identity. It’s like you’re constantly looking at the world and how to navigate different spaces in it. You try things on, you know, like you look at it and you see what you want and you decide how you feel about it and you maybe take a little bit and toss the rest away.

Lisa Corinne Davis, Schamtic Sham, 2020, acrylic and oil on paper,14 x 12 inches

Lisa Corinne Davis, Bogus Basis, 2020, acrylic and oil on panel, 20 x 16 inches

SM: Identity is front and center on so many levels right now, culturally, racially, nationally. Meanwhile, your paintings don’t call out their own gender or racial identity or sexual orientation in any overt way. And you’re making paintings that are navigating this in-between space, abstract on one sense while riffing off of real world conditions in another. What does that feel like?

LCD: All of a sudden, for the first time in my life, I’m a “black woman”, writ large – because of current culture. So now I’m thinking, okay, well, what does that mean? I’m not running away from it, it’s so who I am, but I’ve had to think about it again. It’s about perception. Right now people need to perceive me that way.

On some level, I can’t paint anything beyond what I am. The paintings don’t sit quietly in a room. They are always re-forming themselves, adjusting to someone’s perceptions over time.

“Lisa Corinne Davis: All Shook Up,” Pamela Salisbury Gallery, 362.5 Warren Street, Hudson, NY. through November 2, 2020.

About the author: Born in Kolkata, India, Sangram Majumdar is a Professor of Painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art.